Transcript of an interview between Renée B. Adams, Professor of Finance at the Said Business School and artist Nicola Green in relation to Nicola Green’s exhibition Unity at Zuleika Gallery, November 2020 - March 2021.

This interview was recorded on Thursday 14th January, the week before President Biden's Inauguration on 21st January 2020.

Renée Adams

Given all the events that are going on in the US, my most burning question at the moment is how do you view this exhibition in the context of what is going on right now?

Nicola Green

I’ve been reminded of when I first spent time on Obama’s first election campaign back in 2008. I spent a huge amount of time talking to often quite elderly African American women, and they told me so many incredible things. Many of them had witnessed Martin Luther King’s ‘I have a dream speech’ for themselves 45 years before 2008. We’re now 12 years after 2008 and they were speaking in a 50 year timespan. They foretold where we are now, so right now I feel I am living in those conversations that I had with those incredible women back in 2008. They talked about what it meant to them, Obama being elected, what a big deal a lot of it was 45 years after the height of the civil rights movement. But they also talked about how we wouldn’t solve problems and what the backlash would be. Obama himself talks about a long arc of time and my work is about how long term hope and change really are. As human beings we want our hope and change to be fulfilled very quickly, and we want to see effects very quickly, but actually sometimes it can take generations.

In some ways I’m not surprised by the events of the last 4-5 years as I had had it explained to me that it was going to come so I was prepared. A lot of the themes that have been contained in my work have been brought to the fore and lots of people are looking at it right now and understanding it in a way that perhaps when I made it 12 years ago, it wasn’t fully understood.

Renée Adams

Do you view it as symbolic to have this exhibition now?

Nicola Green

For this exhibition I made Unity 1 and Unity 2 which are a development of my circle of hands from the ‘In Seven Days… ‘ series - ‘Day 1 – Light’. I’ve made them with red and blue thinking about American politics specifically, and thinking about how as human beings we come together and we can hold completely opposing views. Most of my work is about: how do we hold completely opposing views? Right now in this point in time in American politics and with this particular inauguration coming up, that’s a very prescient and pertinent question that everybody is thinking about - it’s on the news all day every day, not just in America, but around the world so. Even though I made a lot of the work [in this exhibition] in 2008, 2010 and 2012, the questions that are on everyone’s mind right now with this particular election, and in particular this inauguration, are contained in my work. I see this a really interesting time to be reflecting not just backwards but also forwards.

Image: Unity I and Unity II, 2020,

Back in 2008 I was pregnant with my first child, and as a white mother of mixed race children - my husband is black - I was really concerned about how their experience would be completely different to mine, just because of the colour of their skin. I wanted to make this work on their behalf. They were too young to witness and understand what was going on, nevermind to be there. My husband knew Obama well, and I became increasingly focussed on thinking about what his election would mean for my children that had just been born. Not just them but their entire generation.

I then realised that there were tonnes of people following that election – the whole world was watching it – the world’s photographers and writers. I then realised that I had a very particular perspective: I wasn’t commissioned to take photos for the cover of a magazine, nobody had asked me to do it, but I had an insider/outsider access. I knew him [Obama] personally - he agreed to me being on the campaign - and I was trusted with an incredible amount of access. At the same time, I wasn’t American, I wasn’t invested in the politics of whether he won or didn’t – it wouldn’t affect me in the immediate political sense. I got to go, be on the campaign, leave, come back to the UK and had a huge broad perspective.

I was very focussed on making work […] that would be relevant and that you could learn from and think about its meaning over the next 45 years, and actually we’re only 12 years into the next 45 years. This feels like a really good and interesting moment to sit and reflect and think about what is happening now and think about all the themes contained within this work, which are ongoing and are not defined to one moment in time. Specifically my work is about their legacy and how that legacy will continue forever. It’s not made with just one ‘moment’, it’s not tied to one moment.

Renée Adams

As you know I’m doing some work on art and gender and I’ve been thinking more and more about the role of art as a catalyst for cultural change, so I find it fascinating that you’ve done this work and that you’re showing this at this point in time. It’s not just interpreting or witnessing, it is potentially serving as a catalyst.

Nicola Green

When I was making this work, I spent 3 years in monastic silence. I didn’t tell anyone I was making this work, that’s how much I didn’t want the work to get drawn back into the day and the moment. When I was making it and at the point I had finished it, I felt I wanted my children and my children’s children to look at this work and think about ‘what can we do’? This work can be read on many levels, but on one level it’s ‘What does it take to achieve something impossible as human beings?’ I had this imagining of my children, thinking about the environment, how can we do something that seems impossible and against the odds? This is a story that things can be done when people come together, it’s not perfect, but they really can be done. I had imagined how this work could serve future generations, to think about their own issues that have nothing to do with party politics. I see this work as quiet, ongoing activism. Objects that we have made are the things that last the longest. We know most about Romans, Greeks and Byzantines from the objects and art they left behind. That’s how we learn about our history and are able to move forward and make progress. Art and cultural objects have an incredible ongoing activism. I think this is often overlooked.

Renée Adams

I totally agree. I think this is a fascinating thing to think about, especially now with the Black Lives Matter Movement and so many issues around gender equality. If you think about what are the best ways to effect change it seems Art is definitely one of the really important ways to try to change culture.

What fascinates me almost more than the art itself is you, going out there and achieving something that very few people will have thought of doing and accomplishing. That in itself is activism and role modelling. What do your children think and how do you think this work will have affected them?

Nicola Green

The piece ‘Struggle’ that is part of the ‘In Seven Days… ‘ series, is Obama’s struggle, it’s all the struggle that went before him…. But on a personal level it’s also my own struggle. […] In practise making this work and going on the campaign, I say it like it was easy, but it really, really, really wasn’t. My husband is a black politician here in the UK, David Lammy, he knew Obama and he came back from a trip in America and said this friend of mine is thinking about running for president. So I had access to him. After nearly a year and half of thinking about it, and why I wanted to follow him on the campaign, I was able to ring him up. I rang him up, told him what I was thinking, and asked if I could have access, and he said, ‘Sure’.

Image: Struggle, Light, 2010,

After that, I didn’t get to speak to him about it very much. I had to speak to all his staff. His staff were like ‘no’. ‘Why would we be wasting our time with an artist? It’s risky, and who are you, and what are you going to do, and we don’t have any control over it.’ But because he [Obama] had said yes, I was able to speak with his team and eventually I persuaded them to let me go on one trip. I went to the DNC when he got the nomination. I would then hassle them and phone them and eventually they might come back to me and go ‘Well, if you’re in Philadelphia or New Hampshire at 7pm tomorrow we might be able to let you in’. I was sitting at home breastfeeding my second son when this started. I stopped breastfeeding him to go online to see if I could get a flight and go to some unknown bit of American that I’d never been to. I didn’t know where I would stay, I didn’t know where and I had no certainty on whether I would get let in. It was on a personal level really, really hard. I learned that by imagining something and just showing up and making it happen, then all kinds of incredible things can happen. I spoke to him [Obama] pretty much every time that I went and he became invested in the work, and he now has the work and loves it, and it’s important to him. On a personal level it was a huge struggle and a huge achievement, especially as a woman who had just had children. I was incredibly lucky to have a husband and family that actively encouraged me. This work, as a woman, as a mother, as an individual, was a huge achievement for me.

For my children this work has been a massive part of their life. I remember vividly when I had decided I wanted to make it, having newspapers and magazines on our kitchen table, and with having never seen black men on the cover of magazines or newspapers, there was Obama, every day, every week. My boys and my daughter, they’ve grown up with that. That did not happen until literally their generation. We don’t know yet what the long term legacy of that is, but that is huge, it’s a massive change, it’s not one you can instantly measure. My children have grown up with this work which is not so much about Obama, but it’s about them. They are on their own journey of understanding their mixed heritage. I know it’s a big deal for them that their white mother has spent the last 15 years thinking about this topic, not just for them as a mother, but in my workplace, and that is a big deal.

Renée Adams

There are so many interesting things about the story. Looking at your work, the fist [Struggle] actually also reminds me of the Rosie the Riveter-type images and what I think is interesting about the fist is that you can’t really tell if it’s a man’s fist or a woman’s fist. So while you were in Obama’s campaign, some of the images strike me as dealing with the issue of masculinity, but also bringing in the gender angles, it’s interesting. You mentioned that you talked to many black women, would you like to say something about how you view them?

Nicola Green

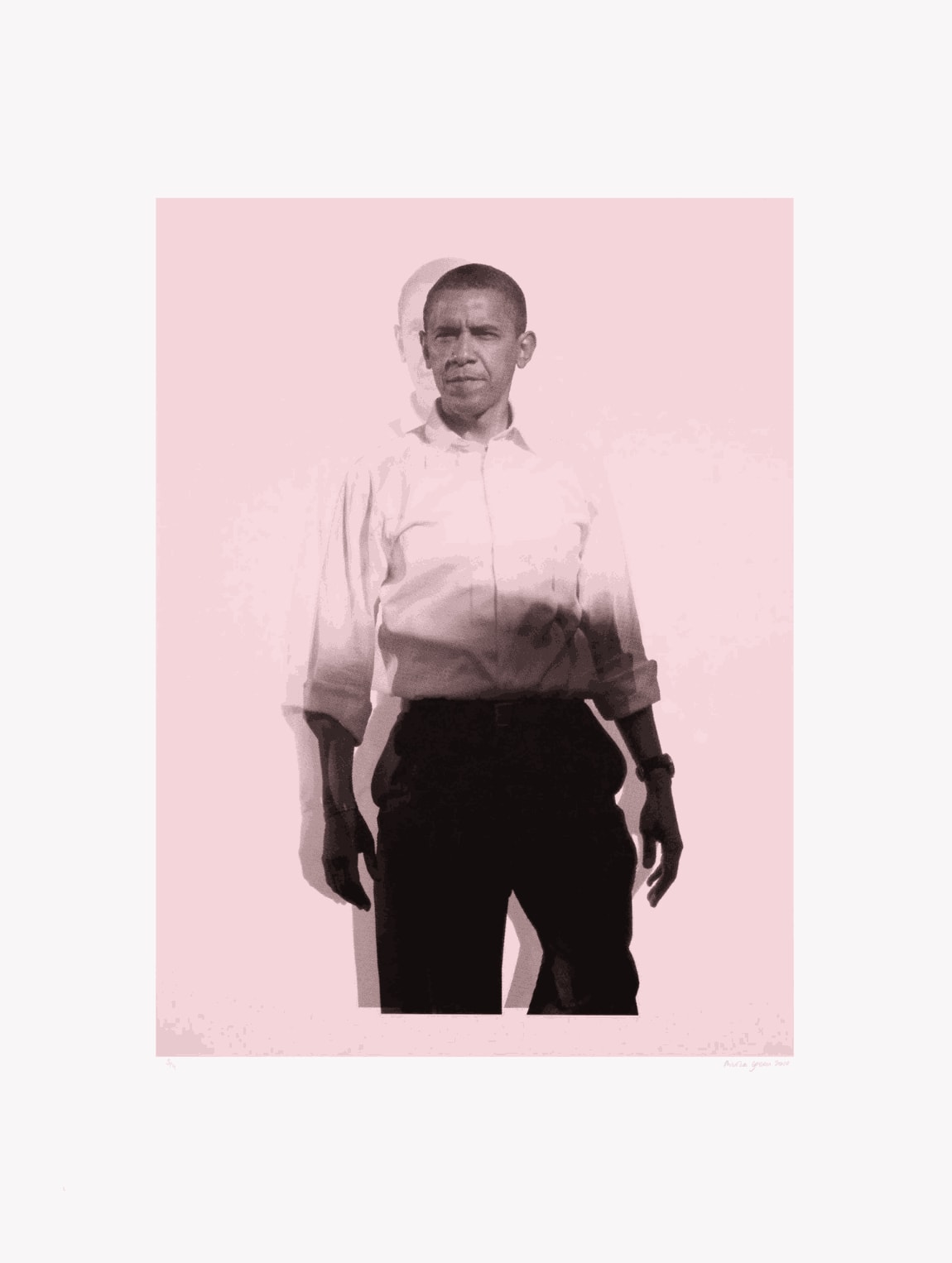

I was really, really aware that I was not American making this work, so in a sense I represented the global community, and I was making work that was about all of us. This story, they said at the time, was the most watched in human history. It affected everybody because it was the first non-white leader in the Western World – a huge deal – especially after all the events of the 20th Century. The whole world was watching, whether they agreed or disagreed, whatever their politics were, everyone was watching, everybody was a part of this story in one shape of form, and of course that included women. And I was a woman, on that campaign making a story about, primarily a man – and politics has generally been a man’s world – slowly it’s changing. I was very aware of wanting to think about what everybody’s part in this story was, [a story] about race and skin colour, it was about age - I was doing it for my babies - as well as the older people whose stories I listened to, and gender, men and women. Women were obviously a massive part of that campaign and African American women had an extraordinary voice in that campaign. In terms of the imagery, I had hundreds of drawings from the campaign – sketches and photographs. I had a huge amount of material. I spent two years researching all these themes and thinking about them. I then came up with these seven images. Each one has so many layers to it, we could do a talk on each one. The raised fist is in many ways most associated with civil rights, Mandela and Martin Luther King, and of course the Olympic salute and more recently Black Lives Matter. The feminist movement in the 60s used it after the Miss World pageant. The Republicans have used it, the Socialists have used it. It’s a symbol of power and change and struggle that has been used by most peoples across the world through time in different ways. Its history is incredibly powerful and women’s part of that history is just as important as mens. In fact this is a drawing of Obama’s hand. I did intentionally make all of these works universal, iconic images. While they are all rooted in specifics, they reference a history of struggles and movements, including feminist. Obama, Pink was about how he redefined masculinity in relation to power and race. The hand symbol is in all of the works and is central to each. I wanted to focus on semiotics and how we communicate non verbally. They say that at least 2/3rds of our communication is non verbal. Here was a campaign where everybody was reporting his [Obama’s] words and his oratory. But I was struck by how much of it was non-verbal. There were people watching this all over the world who didn’t speak a word of English but were still being communicated to in so many ways. I was focussed on what were the messages and the codes, and how each of us was decoding the messages in different ways around the world, and for different reasons. I focussed on the hand gestures - hand gestures are totally universal to us all - wherever we come from.

Image: Obama, Pink, 2010, two-colour silkscreen print with water-based ink on Somerset white cotton paper 225gsm, 133 x 101.5, Edition of 4.

Renée Adams

What strikes me about your work, and what appeals to me as an academic, is how research intensive your work is. It’s pretty incredible. I wonder if you can elaborate on your process in terms of research, and how do you view the importance of research, especially in a time when people dismiss research and facts and don’t think experts have anything to say any more?

Nicola Green

I don’t think you can dismiss research. It’s not possible for each individual to be an expert in everything. It’s simply impossible and that’s why we have different professions. You wouldn’t go to your next door neighbour to cure your cancer. Research and expertise is crucial. We have to pool our resources - there’s not enough time. Expertise may be less valued right now - that may be the case - but it must be temporary - it can’t be sustainable. The opposite of expertise is opinion. Opinion is not based in facts - you’re dismissing evidence, facts and research to assert one opinion over the other. Research and expertise is crucial to us achieving anything substantial as human beings. With this pandemic everyone is very focussed on expertise and research. I think it’s dangerous to dismiss research, but maybe I’m biased as I’m very research heavy. I’m interested in research in relation to my work as I’m interested in recording stories so that they last forever. If it were just my opinion - why would my opinion be worth more than anyone else's? Research allows you to bring layers, and other people’s expertise. In terms of ‘In Seven Days…’ I didn’t feel like my opinion was that big a deal in relation to such a monumental story. I wanted to think about what had gone before and what was happening on so many different layers and levels. Each individual work is imbued with that history and other people's ideas. For my practise the research means that my voice is not paramount as I feel like I'm a witness and telling a story and bringing in as many voices as I can. The best analogy I can think of is a war artist. Often war artists work for years before they release their work as it’s such a massive experience and so many peoples’ experience. I’m interested in my work in not being the sole author, but in being a channel for a bigger story. This is much bigger than me, it’s not my story.

Renée Adams

The way you are describing it to me, you sound like you’re a scientist. We sit for years and study issues to discover what we think are universal truths. We also take ourselves out of the picture. People don’t expect this with art. One thinks art is subjective. I think your approach is really interesting, in terms of the research and taking yourself out of the picture.

Nicola Green

It is different to how many artists work. It’s quite hard to articulate and I think you’ve just done that.

Renée Adams

I’ve been dabbling in art in order to survive the pandemic and as a result have become aware of how difficult it is to make art. There are so many dimensions to it. One thing that fascinates me is how do you view the fact that your witness is essential to the creation of the art. I’m reading Susan Sontag’s book on photography, and thinking about the issue of participation. How do you see the witnessing as being essential to what you are doing?

Nicola Green

There is an amazing chapter written by Marian Saunders in the book Encounters about my work, and she decontructs that witness, the tropes, the history of women in religions and religious texts as being the witness and yet not the voice, and references Susan Sontag’s book on photography. I’ve thought so much about what Susan Sontag has written. She talks about how most photography is made implicitly for the universal male gaze and the photographer themselves is quite often an aggressor. Many indiginous communities think you are actually taking something from somebody when you take a photo. I was so aware of that. When I arrived I got to sit right next to Obama. I was not on the press rack. On the press rack they were mostly men with these enormous cameras, they looked like guns or phallic symbols, in your face. There were banks of them. I really understood then in a new way what Susan Sontag was talking about with this aggressor. ‘Day 5 Fear’ is really about exactly that. It’s Obama’s viewpoint - what he saw all this time. I chose consciously to take a tiny instant throw away camera, and every photograph I took on the campaign was taken with this tiny instant camera. I did not want to get stuck behind the lens where I would become that. I wanted to be in the experience as much as possible. I was very aware of not putting the camera up very often. I was also taking sketches and drawings. I was focussed on a lot of what is discussed in Susan Sontag’s book. Although by serendipity I did take some incredible photographs, I kept them back and still haven’t released them as I would have just become one more photographer taking something. I wanted this to be a witness that would serve forever. I think that is why I have sold this work primarily to museums as they are in the business of thinking about what lasts forever and they have a role to preserve our collective witness as a society.

Renée Adams

I can imagine there will be material here for many years. Could you let us know a little about what you are doing going forward, what inspires you and what topics you are looking at.

Nicola Green

I’m nearly 50 and Encounters took me 10 years. I’m very aware that I only have a few projects left in my life, and I really have to carefully think about it. I’m interested in witnessing the stories that are happening now that will have profound impact for years to come: the stories where we don't really understand what their impact will be. I’m trying to choose the topics where being a witness is being important and where I can add something. Lots of the work I have done has been about men, so I’m also thinking about how to make a series of work in response to the last 20 years of my practise. Gender and the Environment are topics I’m currently working on.

Renée Adams

My personal interest is gender of course so I’m very excited to see what comes out of that. I think your work has a lot of potential to be a catalyst, so the more of that the better.

ENDS

With thanks to Nicola Green and Professor Renée B Adams. Images courtesy of The Artist. Watch a video of this conversation here:

Watch video

Nicola Green - Unity is live to view until 14 March 2020. View the exhibition, here

Watch a video showing Installation Views